Study Design and Methods

This study had two specific aims:

Aim 1. Investigate the process of HIV disclosure and the barriers and facilitators of caregivers’ readiness to disclose through qualitative inquiry with adult caregivers of HIV-positive children, adult caregivers and adolescents living with HIV, and primary care clinic staff.

Aim 2. Develop an instrument to assess a caregiver’s readiness and self-efficacy to disclose that can be used by trained lay and professional health workers in primary care settings to inform their use of HIV disclosure interventions.

Working in Zimbabwe’s Masvingo Province, we conducted formative qualitative research to understand the factors underlying caregivers’ readiness and self-efficacy to disclose, how and why this changes over time, how child characteristics including developmental level and health status impact a caregiver’s approach to disclosure, the positive and negative consequences of disclosing experienced by caregivers and children, and the types of support that caregivers and their families are seeking during the process of disclosure and beyond.

We used the qualitative findings to develop a broad survey instrument to assess a caregiver’s readiness and self-efficacy to disclose and potential barriers and facilitators to disclosure, such as their perceptions of the child’s readiness, the health status of the child or of themselves, fear of stigma, or qualities of the caregiver-child relationship. We recruited a cross-sectional sample of caregivers of HIV-positive children, administered the survey, and followed the cohort of non-disclosed caregivers for 12-months. We used the results to develop a measure of caregiver readiness to disclose.

The study protocol was approved by the Duke University Institutional Review Board, the Joint Parirenyatwa Hospital and College of Health Sciences Research Committee, the Medical Research Council of Zimbabwe, and the George Mason University Institutional Review Board. All study participants provided written informed consent.

Aim 1: Formative Qualitative Study

The purpose of this phase was to develop a pool of survey items that measure constructs thought to influence a caregiver’s readiness to disclose a child’s serostatus to the child.

Setting and Participants

We recruited 73 health workers, 18 adult caregivers of HIV positive children, and 17 HIV positive adolescents from health clinics in Bikita District in Zimbabwe’s Masvingo Province to participate in 32 focus group discussions about disclosure between August 19, 2015 and January 23, 2016. Bikita District is located almost 400 kilometers from the capital of Harare in a rural region near the border with Mozambique best known for mining. In 2016, the adult HIV prevalence rate in Masvingo Province was estimated to be 12.9%, down from a high of 16.6% in 1998 [1]. Masvingo is one of the poorest provinces with more than half of the population falling in the poorest two wealth quintiles [2].

Health worker sessions were open to nurses, patient advocates called Community HIV & AIDS Support Agents (CHASAs), primary care counselors, and other staff who provide services to HIV positive children and their caregivers. All 23 health clinics in Bikita providing HIV-related services participated.

We conducted caregiver and adolescent focus groups at 3 of the 23 health clinics in the district. To be eligible for shortlisting, clinics had to (i) be accessible by public transportation, due to constraints on study logistics; (ii) have more than 20 children younger than 18 years of age currently enrolled on antiretroviral therapy; (iii) have a CHASA available to help with participant recruitment; and (iv) offer support groups for adults living with HIV. Five clinics met these criteria, from which we selected three that represented differing levels of service: one clinic with a primary care counselor onsite, one clinic with a “star” rating from a local HIV and AIDS service organization representing exemplary care, and one with neither characteristic. These three clinics provide services to patients from three geographically distinct catchment areas in the district.

We attempted to recruit caregivers representing each combination of caregiver and child disclosure status as shown in the table below. First, we created a sampling frame at each clinic by asking clinic staff to review their registers and make a list of children between the ages of 6 and 15 enrolled on ART. This list remained with the clinic and did not generate any new information about patients. We created a de-identified copy of each list and issued a new study case number. Children were stratified according to gender, age, and their caregiver’s support group membership. We used a random number generator to rank the order in which eligible caregivers of these children would be invited to participate. A clinic representative known to patients then contacted the caregiver, informed him or her about the study, confirmed the child’s disclosure status, and extended an invitation to participate in the appropriate group. The clinic’s recruitment lists were destroyed following data collection activities. We were unable to recruit a group of caregivers who were members of an adult HIV support group and reported that they had not disclosed their child’s status to the child.

| Child.knows.serostatus | Yes | No |

|---|---|---|

| Yes | 2 | 2 |

| No | 0 | 2 |

We also recruited a convenience sample of HIV positive adolescents aged 14 to 18 years from the membership of three HIV support groups that meet at one of the clinics. We conducted a separate discussion session with each group.

Procedures

Literature Review

We reviewed the empirical literature on pediatric HIV status disclosure and created a list of 175 predictors, facilitators, barriers, and consequences of pediatric disclosure (typically using statistical significance as a filter). We then collapsed similar concepts into a set of 78 unique cover terms (or phrases), gave each cover term a unique identifier, and wrote each cover term (in English and Shona) and identifier on a blue index card (“literature cards”). For instance, research suggests that one facilitator of caregiver readiness to disclose a child’s status to the child is the child’s severe immunosuppression [???]. We created a cover term based on this finding called “child’s deteriorating health condition facilitates disclosure”. See the study repository for a complete list of literature cards.

Health Worker Discussion Groups

We conducted 23 discussion groups with 73 health workers. The mean group size was 3.2 people (SD=0.7).

Free Listing

During each health worker discussion group, participants were invited to engage in a free-listing activity where they would suggest factors that facilitate or hinder disclosure. The facilitator introduced the activity by saying:

We would like you to list as many things about HIV disclosure that come to mind. Examples might include characteristics of caregivers or children that make disclosure easier or harder. Or they could include details about a family’s situation that promote or prevent disclosure. You could also list steps that caregivers must go through in deciding to disclose. These are only examples, however. We will keep prompting you to think of more ideas, and we will write down each one on a card. There are no bad ideas. We want to write down as many ideas as you have. We will probably pause from time to time to ask for clarification or to ask you to say more about a particular card. When we are done, we should have a stack of cards in front of us that reflect your ideas and experiences. Do you have any questions?

The facilitator wrote down each concept on a separate white index card and periodically probed for meaning and examples. The cards generated during these sessions were referred to as the “local cards” to differentiate from the “literature cards” generated from the literature review.

Card Sorting

At the end of the free listing exercise, the facilitator spread the blue literature cards and the white local cards on the table and attempted to match each local card to 1 of the 78 literature cards. Matching sets were removed from the table, and the remaining non-matching literature cards were presented to the group for discussion. Participants were asked to indicate whether they would accept or reject each card as relevant to pediatric HIV disclosure in their context. With the exception of the first discussion group, the facilitator also presented the non-matching local cards generated in every previous session for the group’s consideration. The facilitator used this activity as an opportunity to probe for additional details.

Endorsement Scores

At the conclusion of all health worker discussion groups, we constructed mean endorsement scores for each literature and local card. Literature cards with direct matches to a local card were assigned a value of “2”. Literature cards that did not match a local card were either accepted (“1”) or rejected (“0”). Therefore, literature card ratings could range from 0 to 3. We constructed a mean score for each literature card by summing each group’s rating of the card and dividing by the number of group ratings. We took a similar approach to constructing a mean score for each local card that did not match a literature card.

Caregiver Discussion Groups

We conducted 6 groups with 18 caregivers. The average group size was 3.0 people (SD=0.6).

Card Sorting

Caregivers completed a card sorting exercise and participated in an open-ended discussion of issues raised, but did not complete the same free listing activity. Instead, the facilitator presented each caregiver group with the subset of 30 cards selected from the larger pool of 78 literature cards and 35 non-matching local cards generated by the health worker groups. The set of 30 cards consisted of the 10 most and least endorsed literature cards and the 5 most and least endorsed non-matching local cards. Caregivers were given the following instructions:

We are going to begin with a brief activity. I’m going to spread out 30 cards with words written on them in English and Shona. Each card describes something related to telling a child about his or her diagnosis of HIV for the first time. Some of the cards describe things that can make this conversation easier, while other cards describe thing that can make this conversation harder. I would like to know which ideas are most and least important in your view. Working together as a group, I would like you to look at all the cards and put them into three piles. Please put the card here [point] if you think the idea is very important or very true, here [point] if you think the idea is somewhat important or somewhat true, and here [point] if you think the idea is not very important or not very true. There are no right or wrong answers. I will just listen as your group completes the activity. When you are done, I’ll ask you a few questions to better understand your decision-making.

Endorsement Scores

Caregivers rated a subset of 30 cards as being of high, medium, or low importance. These ratings were assigned values of “2”, “1”, and “0”, respectively. We constructed an endorsement score for each card by summing each group’s rating and dividing by the number of group ratings.

Adolescent Discussion Groups

We conducted 3 discussion groups with 17 adolescents ages 13 to 18. The mean group size was 5.7 people (SD=2.5). Participants were not asked to complete any free listing or card sorting activities, but were instead engaged in an open-ended discussion about how children learn about their status.

Aim 2: Measure Validation

Research Design

We recruited a population-based sample of 372 caregivers of HIV-positive children ages 9 to 15 years living in Bikita and Zaka districts in Zimbabwe’s Masvingo Province to participate in a survey about disclosure. Using data from this cross-sectional sample, we then identified a prospective cohort of 123 caregivers who said their HIV-positive child did not know his or her HIV status, and we followed this non-disclosed cohort of caregivers through two additional waves of data collection over the next 12 months.

Setting and Participants

The target population for this study was primary caregivers—parents and guardians— of HIV-positive children ages 9 to 15 living in rural Zimbabwe. The accessible population was limited to the subset of these caregivers living in Bikita and Zaka districts in Masvingo Province whose HIV-positive children were receiving antiretroviral therapy (or were in pre-ART). We selected this location because study partner BHASO (Batanai HIV and AIDS Service Organisation) had established relationships with 42 of the 48 HIV care clinics in these districts and supported a wide network of community health workers called CHASAs (Community HIV & AIDS Support Agents) deemed essential for participant recruitment and retention.

Masvingo Province is home to approximately 1.5 million people, 23% of whom live in Bikita and Zaka districts [3]. The demographics of Masvingo are similar to the rural clusters in the 2015 Zimbabwe Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) [2], suggesting that the accessible population from which we sampled may be representative of the target population of rural caregivers.

Zimbabwe continues to experience a generalized HIV/AIDS epidemic with an HIV prevalence rate of 13.5% among adults of reproductive age in 2016 (down from a peak of 27.7% in 1997); the adult HIV prevalence rate in Masvingo is estimated to be slightly lower at 12.9% [2]. In 2015, the prevalence of HIV among children aged 0 to 14 years was 1.8% nationally and 1.5% in Masvingo [2].

Procedures

Cross-Sectional Study of Pediatric HIV Disclosure Prevalence

At the time of this study, it was estimated that nearly 9 out of 10 HIV-positive children in Masvingo were enrolled in ART [1]. This made clinic-based recruitment a valid strategy for obtaining a representative sample of caregivers of HIV-positive children.

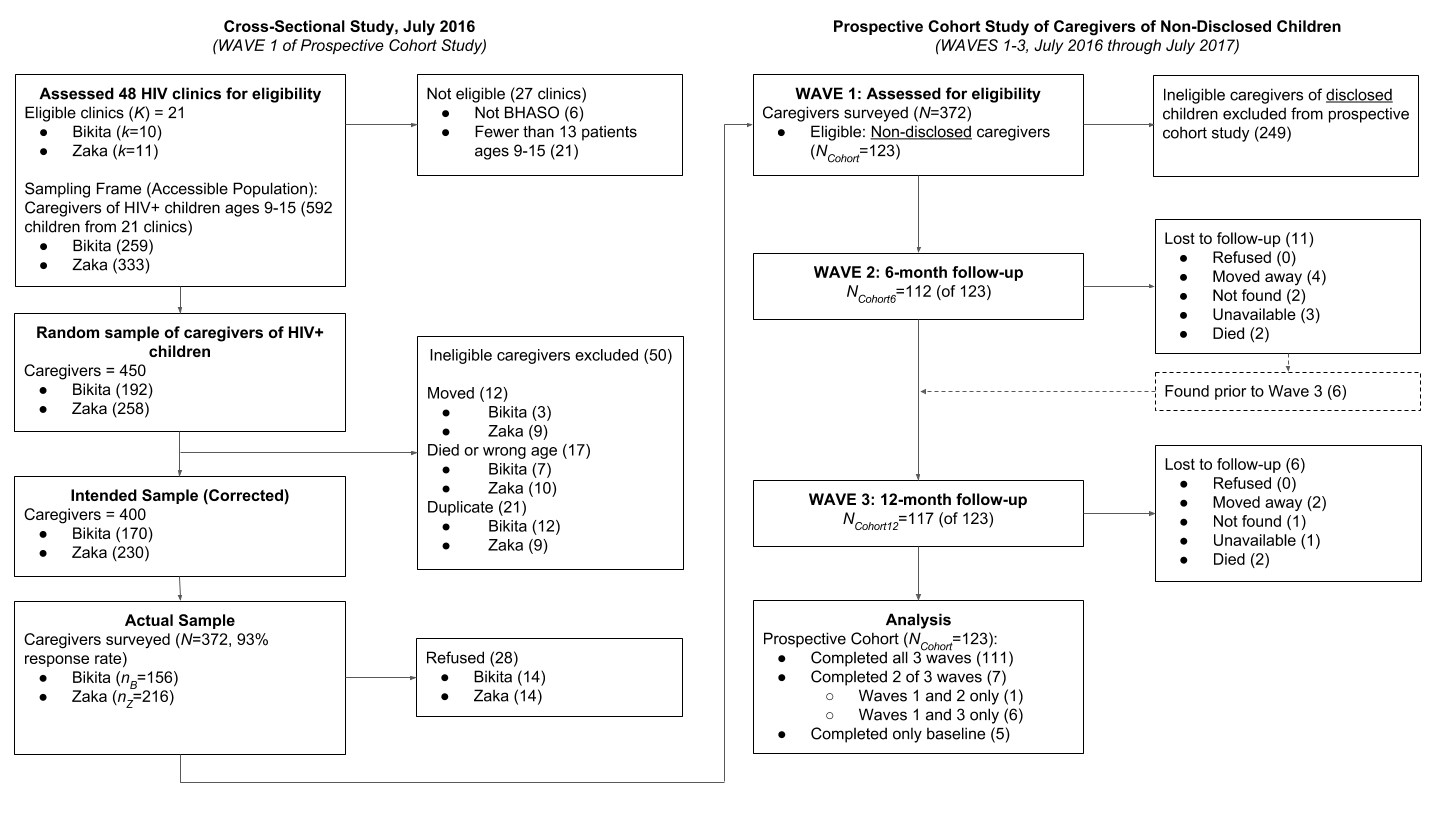

We constructed a sampling frame of pediatric HIV patients receiving ART or pre-ART services at 42 of the 48 HIV care clinics in Bikita and Zaka Districts; the 6 excluded facilities were not part of the BHASO network. Once we had an initial list of patient load by clinic, we excluded an additional 21 facilities that provided HIV care to fewer than 13 patients ages 9 to 15. From the remaining 21 clinics, we used ART and pre-ART registers to develop a sampling frame of 592 eligible children (259 in Bikita and 333 in Zaka). We then used stratified simple random sampling by district (proportional to district size) to select a random sample of 450 children; the target sample size was driven by the needs of a larger study on disclosure readiness. We worked with CHASAs assigned to each clinic to update this sample through the removal of children no longer living in the district, children who had died, and duplicate records. After these corrections, the intended sample consisted of 400 children (under the care of 400 primary caregivers). See the participant flow diagram for additional details.

Participant flow diagram.

Between June and August 2016, our team of Zimbabwean enumerators attempted to enroll and survey caregivers in the intended sample. Trained enumerators were assisted by local CHASAs throughout the recruitment process. Overall, the team surveyed 372 of 400 caregivers, a response rate of 93.0%. All surveys were conducted individually in a private setting at the HIV clinics where caregivers pick up medications for their children. Enumerators read each survey item aloud in Shona and recorded participants’ responses on an Android tablet running ODK Collect software [4].

Prospective Cohort Study of the Disclosure Process

Using data from the first wave of data collection, we identified a cohort of 123 caregivers who said their HIV-positive child did not know his or her HIV status, and we followed this “non-disclosed” cohort through two additional waves of data collection over the next 12 months. We used the procedures described above and attempted to survey all 123 caregivers in this cohort at 6-months and 12-months following the first wave of data collection.

Measures

See here for a link to download the survey files and data dictionary.

Caregiver and Child Demographics

We used relevant modules from the 2015 Zimbabwe DHS questionnaire (Phase 7) to collect demographic data on participants, their children, and their households [2].

Caregiver-Reported Pediatric HIV Disclosure

We asked a series of questions to assess what the caregiver believes the child knows about his or her HIV status and condition, when the child learned this information, and from whom. We also asked whether the caregiver wanted the child to learn this information when they did. Specifically, we probed whether the child knows: (a) that he or she has a chronic condition requiring medication; (b) that he or she has a medical condition called HIV; (c) how he or she was infected with HIV; and (d) that he or she can spread the virus to others. “Partial disclosure” in this study refers to knowing (b), (c), or (d), but not all three. “Full disclosure” refers to knowing (b), (c), and (d) [5]. We use the term “disclosed” throughout to refer to children who know they have a virus called HIV to be consistent with other studies of pediatric HIV disclosure, but we also report results for partial and full disclosure.

For caregivers of disclosed children, we asked whether they found out their child’s HIV status before the child, on the same day as the child (e.g., in cases of disclosure by clinic staff), or after the child. This is an important distinction because we were interested in assessing caregivers’ preparation for disclosure, and caregivers who found out after or on the same day as the child had no time to prepare for disclosure.

For caregivers of non-disclosed children at Wave 1, we asked about their intentions to disclose their child’s HIV status within the next 12 months. We also asked these caregivers (yes or no) whether they had begun to assess their child’s readiness for disclosure, taken any steps to prepare their child, consulted with a health care worker about disclosure, or made a plan to disclose.

During first two survey waves, we realized that caregivers were keen to tell their story outside the confines of the questionnaire. In the final wave of the prospective cohort, we trained the enumerators in active listening and encouraged them to take notes about caregivers’ stories shared throughout the survey. At the end of each day, a trained qualitative interviewer collected these stories from the enumerators.

Caregiver-Reported Worries about Disclosure

We created a series of 15 items to assess caregivers’ worries about disclosing the child’s status to the child. For instance, “I worry that telling [him/her] will make [him/her] too sad.” Caregivers responded to each item on a 4-point scale from (0) ‘not at all worried’, (1) ‘not very worried’, (2) ‘somewhat worried’, or (3) ‘very worried’.

References

[1] UNAIDS. AIDSinfo 2017.

[2] Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency, ICF International. Zimbabwe Demographic and Health Survey 2015: Final Report. 2016.

[3] ZNSA. Zimbabwe Population Census 2012. Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency; 2012.

[4] Brunette W, Sundt M, Dell N, Chaudhri R, Breit N, Borriello G. Open Data Kit 2.0: Expanding and refining information services for developing regions. 2013.

[5] Funck-Brentano I, Costagliola D, Seibel N, Straub E, Tardieu M, Blanche S. Patterns of disclosure and perceptions of the human immunodeficiency virus in infected elementary school-age children. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine 1997;151:978–85.

[6] Wiener L, Mellins CA, Marhefka S, Battles HB. Disclosure of an HIV diagnosis to children: History, current research, and future directions. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics 2007;28:155.

[7] Atwiine B, Kiwanuka J, Musinguzi N, Atwine D, Haberer JE. Understanding the role of age in HIV disclosure rates and patterns for hiv-infected children in southwestern Uganda. AIDS Care 2015;27:424–30. doi:10.1080/09540121.2014.978735.